Liberal Comfort Blankets

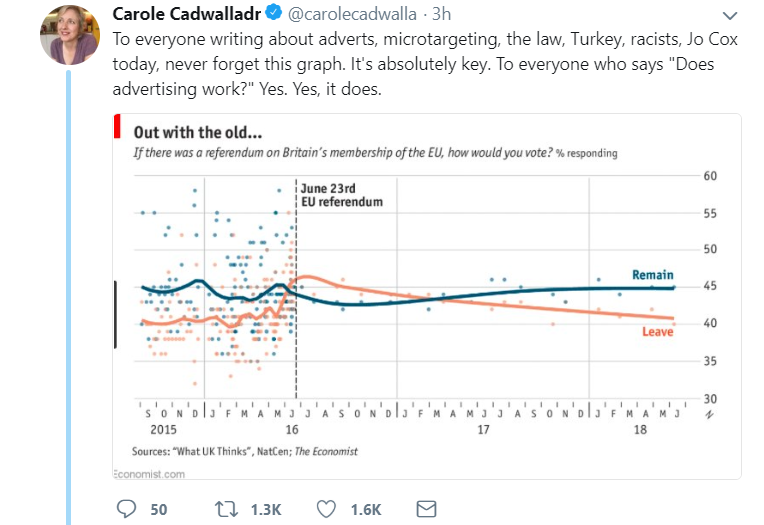

Carole Cadwalladr posted a nonsensical tweet today showing the swing of opinion from Remain to Leave during the EU referendum campaign and claiming this as evidence that the Leave advertising worked.

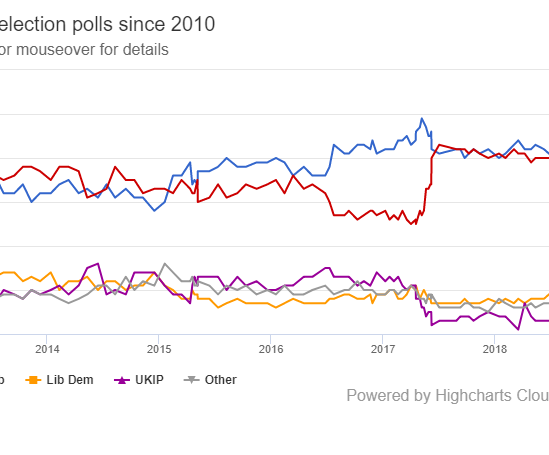

This is a ludicrously childish assumption of cause and effect by Cadwalladr. Consider this graph showing the even more spectacular leap of support by Labour during the 2017 general election campaign. Yet the Tories vastly outspent Labour on advertising.

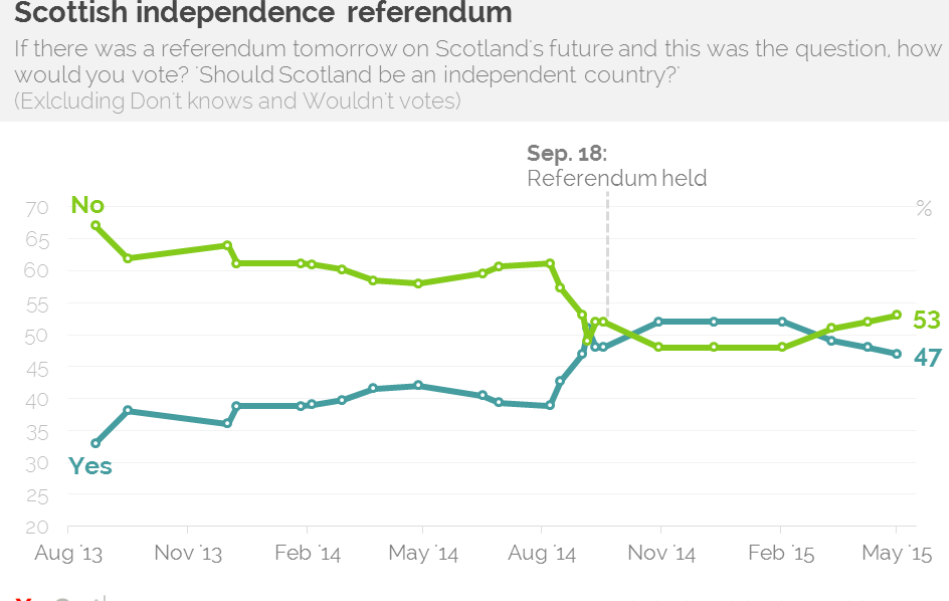

Then look at this graph of the Scottish Independence Referendum, where again No outspent Yes on advertising but opinion swung the other way.

Carole Cadwalladr has done excellent work on the Cambridge Analytica and Facebook data sales scandals, revealing dark doings that needed to be exposed. But the claim that advertising spending has a decisive effect on polling intentions is very dodgy indeed. In fact, looking at the examples of the Scottish Referendum and General Election, using the Cadwalladr induction method you would conclude that advertising spending is counter-productive.

But Cadwalladr’s foolish tweet today is more than an attempt to enhance the importance of the research of Carole Cadwalladr. It is part of a continuing effort by the liberal elite to find simplistic reasons why their views were rejected by a major section of the general populace in two seismic political events – Brexit, and the election of Donald Trump. The elite are seeking to comfort themselves with the idea that happenings of very marginal significance – Cambridge Analytica’s audience research, or 13 Russians allegedly trying to hack unspecified info – were in fact massive factors that explain the electorate’s “deplorable” behaviour.

For what it is worth – and perhaps it is not worth much, though it is worth more than Cadwalladr’s logical fallacy – my own view is that hatred of the political class, by a population which has come to realise it is exploited, was a major factor.

In the Brexit referendum, Remain made the fatal mistake of being fronted by detested politicians – Nick Clegg, Will and Jack Straw, George Osborne, Tony Blair. The chance to kick these people proved irresistible. Similarly Hillary was the most detested machine candidate the Democrats had available. By contrast, while the “authentic” personas of Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage may be fake, they were well placed to tap into the anti-politician mood.

This also explains why Remain did much better in Scotland, where it was headed by the SNP’s far less detested politicians who are themselves regarded as anti the UK establishment

Finally, the key factor that unites all the three opinion poll charts above – General Election, Brexit and Scottish Indyref – is that opinion swings very fast indeed inside the period of broadcasting restrictions, when broadcasters have to give at least a semblance of fair time to the view which the Establishment generally derides. Unlike the advertising explanation, which works in only one out of three cases, the hypothesis that broadcasting restrictions redressing establishment bias is the most important factor, would appear to work very well in all three cases.