France is a standing affront to neo-liberals. Despite a failure to bow down to deregulation, despite extensive worker protections, despite complex health and safety, environmental and building regulations, despite strong and legally entrenched trade unions, France persists year in year in having productivity levels 20% higher than those achieved by unprotected, deregulated Britons. Despite the fact French workers put in 15% less hours per week, and refuse to be less Gallic.

You can find right wing economists who attempt to explain this away so as to make it consistent with the neo-liberal narrative. The most hilarious right wing propagandists like Professor Ryan Bourne argue that this is because the French economy, due to over-regulation, does not produce enough low skilled jobs. This is nonsense. There are not far less people picking vegetables, sweeping streets, serving coffee or washing restaurant dishes in France. A related argument is that high productivity somehow causes high unemployment. This is based on a strange fallacy that an economy is of a fixed size. If economic output was limited to x, then using less people to produce x would indeed cause unemployment. But I cannot readily conceive how stupid you would have to be to believe that. No, unemployment in France is caused by insufficient demand, which cannot be caused by high productivity. The answer to unemployment plus high productivity is a stimulus from public spending.

The truth of the matter is that deregulation does nothing to increase productivity. What deregulation does do is increase corporate profits, by decreasing workers pay and conditions, and decreasing public health and safety and environmental benefits. Deregulation transfers monetary and other goods from people to corporations. It is just a lie that it is anything to do with productivity – indeed the evidence is that a workforce with no job protection and few other rights is demoralised and less productive. That is certainly the obvious conclusion to draw from the comparison between France and the UK.

The concern on the left in France is that Macron is a creature of the corporations who wishes to introduce Anglo-Saxon style deregulation into France. This is, in a word, true.

Deregulation is a bad thing because it vastly reduces a whole stock of public goods.

Where confusion has arisen in public discourse is the notion, propounded also by neo-liberals, that globalisation and domestic deregulation go hand in hand. They do not and there is no reason at all that they should.

There are many definitions of globalisation, but I use it here as meaning the increasingly free movement of goods, capital and people around the globe. In that sense, I am a strong advocate of globalisation. Yet, at the same time, I am a strong opponent of deregulation.

Trade is a good thing. There are things that grow in different climates, there are raw material resources which make production particularly suitable in a particular location, there is local expertise and cultural flair. Trade has existed as long as men have existed, and is undoubtedly a common good. The increase in trade is a good thing too. There is not a single person in the UK who has not benefited from the massive fall in the consumer price of white and electronic goods caused by globalisation. I am today in Ghana where the availability of technical and trading partners from Turkey, Singapore, China etc, in competition with the traditional powers, is part of the revolution which has transformed the economy and the living standards of ordinary Ghanaians since 2000. The economy here grew by an average of over 7% over that entire period and is about to take off into higher regions again. (After a brief interlude of ultra-corrupt government very much sponsored by the USA and the multinational GE, but that is another story).

Globalisation is caused by a combination of technology and reduction of artificial barriers to trade and movement of people and money. It has beyond any doubt caused a huge amount of economic growth in Asia, and although from a very low base, in Africa too. Africa is the coming continent. The opponents of globalisation are those who wish to see a disproportionate amount of the world’s resources continue to be consumed in the old industrialised countries. They disguise this as protection of the working class.

Immigration does not depress living standards. Again, to believe that it does you would have to be extremely stupid and to imagine that an economy was a fixed size. If immigration depressed living standards, the United States and Germany would be among the poorest countries in the world. It is a complete and utter nonsense.

If it were not for immigrants, there would have been no growth at all in the UK economy for a decade, and absolutely no chance Britain could maintain its pensioner population. Immigration does not depress wages, it grows the economy. To take but one example, Polish immigration has contributed enormously to the British economy and to British society. It has given new economic opportunities to Polish people, and a Polish person is worth every bit as much as a British person. But the competition for Labour is also an upward pressure on wages in Poland, which is a good thing too.

I support globalisation very strongly as boosting the economies and raising the living standards of the entire world. That is the internationalist view.

But globalisation is not synonymous with the deregulation agenda. Neo-liberals have managed to establish in the public mind the idea that globalisation and domestic deregulation are necessarily part of the same process. The left has accepted the fight on this neo-liberal ground, with disastrous consequences to which I shall revert. But as is often my style when I say a truth outside the accepted political discourse, I am going to say this twice.

Domestic deregulation is not a necessary concomitant of globalisation.

Domestic deregulation is not a necessary concomitant of globalisation.

The neo-liberals, whose interest is that corporations rather than people profit from the process of globalisation, argue that domestic deregulation is necessary in the face of globalisation. This is the so-called model of the “race to the bottom”. Whoever pays the least, can shed labour easiest, has least health and safety and environmental regulation, will succeed in the global market. Therefore to face the challenges of globalisation, domestic protection must be dismantled.

I offer two irrefutable proofs that the neo-liberals are wrong:

1) France. And Germany too.

Annoyingly for the neo-liberals, many of the most regulated economies in the world continue to be the most productive countries in the world. This stubborn fact is extremely frustrating for the neo-liberals, and leads them to make fools of themselves coming up with the daftest possible explanations (see Ryan Bourne above). It is also why they are desperate to destroy the French model (see Macron above).

2) TTIP. And more or less every other multilateral trade agreement too.

Why did the neo-liberals have to stuff the proposed TTIP with proposals to destroy regulation within the EU market? If the neo-liberals believed their own propaganda about deregulation increasing productivity, then by a natural and ineluctable process the EU would be doing this as the invisible hand moved them to compete in the globalised market. But actually it is not a natural part of the process of globalisation at all, and has to be forced on by the corrupt political class in the pockets of corporations. Hence the deregulation provisions in the trade agreements, along with other corporation boosting measures like extra-territorial arbitration.

Frequent USA/EU rows over Boeing vs Airbus illustrate my point very well. Each accuses the other continually, and fines the other continually, over state subsidy. But within free trade, why is it of any interest how the state(s) trading mobilise their own internal resources? Again, if neo-liberals really believed what they say they believe, then by subsidising aircraft production a state is damaging its own economy massively elsewhere and opening up other comparative advantage opportunities for its trading partner. It makes no more sense for states trading to try to police their internal mechanisms, than for a car manufacturer to argue about where another car manufacturer places its canteen in relation to its production line.

How a state organises its internal resources, how much it pays people and how it protects its inhabitants from unfair dismissal, pollution or bad food, even how it subsidises a particular industry, cannot give it any unfair advantage across the whole range of trade with another state. The most economically productive and successful states are those which do regulate strongly for worker and general welfare and health, not those who raced to the bottom.

Domestic deregulation provisions are unnecessary, inappropriate and damaging to trade treaties.

You can reject deregulation without rejecting globalisation. That is a largely ignored intellectual position and it is one which the Left needs to adopt if it is to distinguish itself from the far right. In France, Macron represents the neoliberal position of embracing both deregulation and globalisation. LePen stands for the rejection of both. A worrying number of people who call themselves “left wing”, in France, throughout the media, and on this blog, allow themselves to flirt with the notion that LePen’s position is preferable.

The anti-globalisation angle that attracts the left is recidivist. In the name of protectionism it opposes the movement of capital, of goods and, its strongest emotional pull, of people. Here it blends neatly into the fascist agenda.

I argued earlier that those who oppose globalisation are opposing the trends which have pulled a huge proportion of the population of the earth out of extreme poverty in the last decade. I have argued that those who oppose globalisation were happy with a situation where a massively disproportionate share of the world’s economic resources was consumed by those in the first industrial world, and wished to return to that situation. This in itself is an inherently xenophobic position.

But they are also racist in another way. The process of domestic deregulation – a different process to globalisation – has massively increased wealth disparities in western states. The Tories are parroting that the top 1% of taxpayers pay 28% of all taxes. That is because the top 1% of taxpayers consume over 28% of all income.

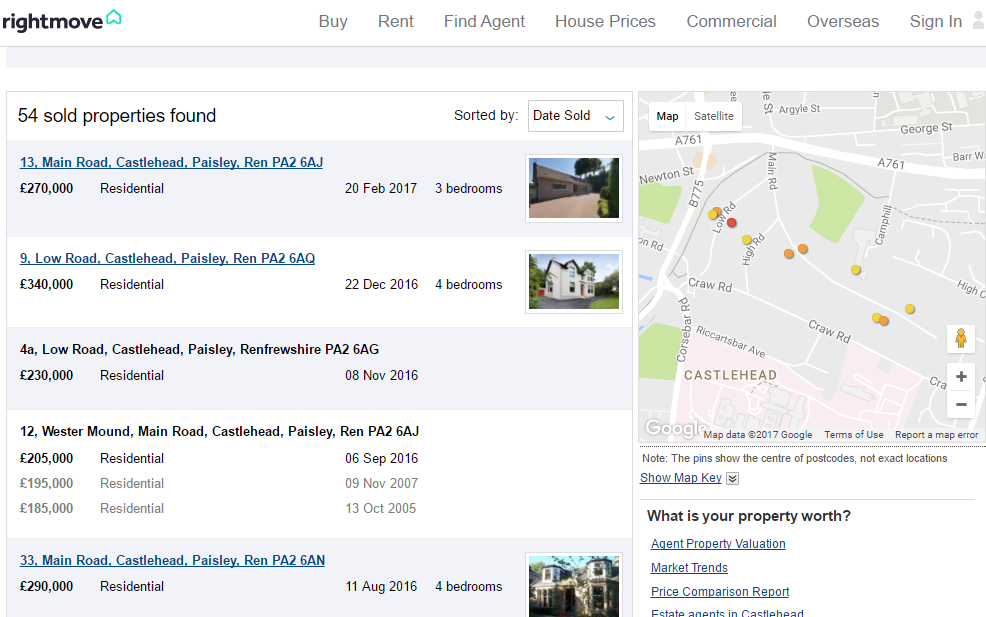

The ultra-rich have distracted the mass of the people, who are suffering increasing and real poverty and an inability to acquire housing and other fixed capital.

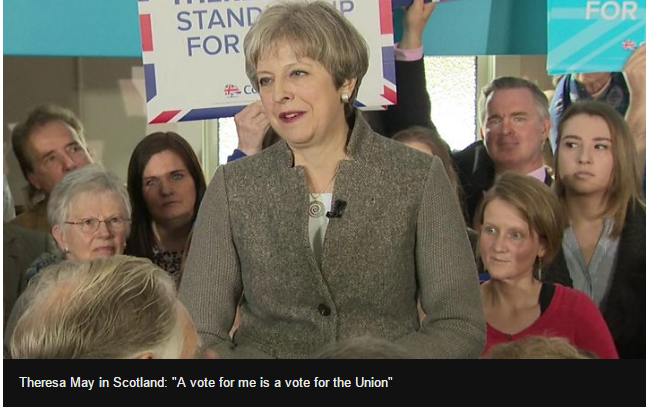

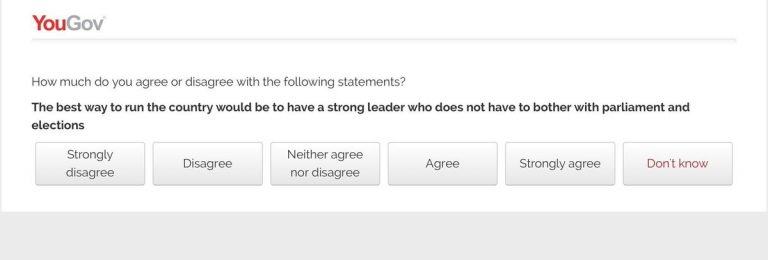

The wealthy and their political and media propagandists have pointed to immigrants and persuaded people that it is not the obscene share of resources sucked out of the economy by the ultra-rich, but rather the productive immigrants who are responsible for their poverty. And people fall for it. This is the attraction of the racist dog-whistle on immigration blown by Trump. LePen, UKIP and now shamelessly by Theresa May and the Tories. Some who consider themselves Left fall for this racism to the extent they are prepared to tolerate LePen.

LePen is a genuine fascist. She is in the tradition of the Nazis and Vichy. Her chosen senior colleagues are Nazi sympathisers and holocaust deniers. She is the grossest of crude Islamophobes. I detest the lies and callousness of neo-liberals, their complete absence of empathy, but there is no moral equivalence between a neo-liberal and a Nazi, and it is ludicrous to pretend that there is. Anybody who does so is not welcome, as I have said, to comment on this blog. I have no desire to associate with Nazis. The rest of the internet is open to you.

The Left has failed to formulate a coherent intellectual response to globalisation, largely because they have fallen for the neoliberal intellectual trap of believing domestic deregulation to be a necessary concomitant. The rejection of internationalism has led some who consider themselves “left” to be attracted to LePen and fascism, at least to the extent they do not recognise her extreme evil. Anybody who has felt that should be deeply ashamed.

Nick Cohen’s book “What’s Left” identified tolerance of Islam as the weakness of the British and European Left. In fact he was diametrically wrong. The weakness is an abandonment of internationalism and a susceptibility to racist anti-immigrant dialogue.